Fellow Partners,

A number of you have asked if you could increase your positions in the fund. Yes, we are still accepting subscriptions. Please reach out to me if you would like to do so.

Thank you for your referrals over the past few weeks. We look forward to welcoming several new partners shortly. If you know others who align with our philosophy and strategy and may be interested in this partnership please connect us.

We also recently launched phronesisfund.com. Feedback, as always, is welcome.

On to the update, which is the first entry in a series on first principles reasoning. Additional entries will be published over the coming weeks.

A company should be viewed as an unfolding movie, not a still photo. Those who focus on the past see only the snapshot and sometimes reach wrong conclusions. If just looking up past financials would tell you what the future holds, the Forbes 400 would be full of librarians.

Warren Buffett

Had enough

I spent the morning reading an investment journal. One well-known author (unnamed here due to my practice of praising publicly and criticizing privately) declared that his ultimate buy-and-hold strategy, previously consisting of 10 equity asset classes, had been refined down to four. “Simplicity itself” was claimed.

Based on asset class returns between 1928 and 2019 [1,2] it was revealed that one could create a portfolio combining four strategies — an S&P 500 fund, a large-cap value fund, a small-cap blend fund, and a small-cap value fund — which never had a loss over any 15-year period [3]. With these four asset classes, one would be set up to “capture a piece of the action” regardless of which individual strategy was leading in any given period. They would also experience the “true peace of mind” that came from reduced volatility throughout the journey.

Much of the rest of the journal followed a similar theme: look backwards, see what happened, and construct a portfolio for the future based on what happened in the past [3]. I’d had enough by the time I reached the end of the journal and sat down to write this piece.

The lessons of history

There is an immense amount we can learn from history. Within capital markets we learn valuable fundamental and behavioral truths and get a sense for how markets and businesses behave and evolve over time.

We see that companies are valued for their fundamental performance in the long run and that markets can behave irrationally for extended periods of time. We also see that markets and businesses behave as complex adaptive systems, such that profitable strategies often lose their profitability over time.

These lessons are immensely useful when we sit down with our portfolio and decide how to invest. Historical data can help us know where to look and what to watch. But it cannot tell us what to do.

Don’t outsource your thinking

All this is to say: we cannot outsource our thinking to historical data. Principles matter enormously. Profit matters; margin matters; free cash flow matters; growth matters; competitive moats matter; management matters. But no one is studying the operations of businesses a century ago to figure out how to operate businesses today. Businesses have evolved. So have markets.

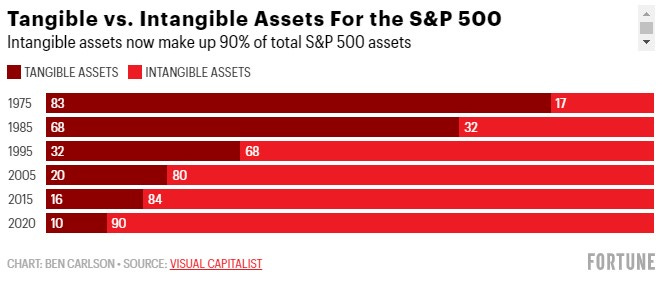

To take a common example: metrics that were immensely useful a few decades ago, such as price-to-book value, are ill suited to our current environment where most of the business value for many businesses is derived from intangible items such as talent, brand, IP, code, and patents, which is not well represented by our current accounting standards and poorly accounted for in the price-to-book calculus. Those waiting around for the market to reach a low price/book valuation before investing may be waiting a long time. This metric – while still useful for certain types of businesses – is ill suited to describe the reality of a market that has evolved through the information age.

This underscores the importance of understanding how investment strategies are defined. For example, a small cap value strategy will use metrics such as price/book and price/earnings to classify companies as “value” stocks. But this is within a present reality where businesses have invested as much or more in intangible assets (vs. tangible assets that show up in price/book calculations) for the past two decades. Price/book has become a less useful (or in some cases irrelevant) metric on which to segment because it fails to account for how business value is created in much of the market. A resulting strategy that uses this metric will be flawed from the start — not because the idea or past performance of such a strategy was poor, but because this approach no longer adequately assesses the way many businesses have evolved to create value.

A similar chain of logic can be used for metrics such as price/earnings. While earnings are essential over time, investments in intangible assets are often long games, absorbing cash in early years resulting in low or negative earnings with the benefit of requiring minimal cash in later years resulting in enormous earnings. Realizing that 90% of assets in the S&P 500 are now intangibles (see chart below for how this has evolved) should prompt careful consideration on the nature of how and when firms are wisest to realize free cash flow as earnings as opposed to investing free cash flow in product, marketing, or other areas that could raise future earnings.

There are plenty of ways to deal with these realities, of course. They require a deeper level of consideration and — importantly — would generally undermine a financial academic’s desire to write a short pithy article about “simplicity itself” and “true peace of mind”. As is always the case: buyer beware.

A better way

The cure? Reasoning from first principles.

These principles are the gold dust of history. We know certain things always matter in the long run (long-term free cash flow chief among them). One of the greatest lessons of history is that markets and businesses are complex adaptive systems. Knowing this, we can study the systems and adapt accordingly.

We should use history as a guide to understand how markets and businesses have evolved — not as a prediction engine to outsource our thinking.

Closing items

As this series unfolds we will cover first principles reasoning in a number of areas: market context, business value, secular tailwinds, portfolio construction, risk management and a number of behavioral traits.

Until next time —

All the best,

John

Founder and Managing Partner

Footnotes

[1] It is odd how commonly accepted the approach of using financial performance and market data going back a century or more has become. Human nature and its expression in capital markets hasn’t changed much. But the attributes, aptitudes, strategies, and business models of firms over the past century have changed enormously. We should be skeptical of placing too much weight on the business performance — and subsequent market performance — of businesses that had very different characteristics vs. businesses today. This is not to say nothing is comparable. Despite dramatically improved logistics and technology, today’s grocers behave largely as much-improved versions of their 20th century counterparts. But what of today’s trillion-dollar giants? A substantial amount of their business value is derived from business lines with zero-marginal cost — something that was impossible until recent decades. Researchers are often too keen to use available data to answer intriguing questions without suitably scrutinizing whether those questions can be answered well with the data.

[2] Another data challenge with returns data over long periods: it is highly sensitive. For example, the author’s data showed that a strategy with a 1.2% higher annual return over the 92 year period analyzed would result in a 270% higher return vs. the weaker strategy. Such is the reality of compounding. But the author also conducted the analysis with nominal returns data — that is, excluding the effects of investment costs, taxes, and inflation. These would have a very material impact on investor returns over such a long period, especially as different strategies would have different cost and tax implications. If we are to use very long periods of time for analysis, we must include all factors that would have a material impact on results.

[3] A common trap in the “build a future portfolio on the basis of the past” is that it assumes the existence of an option that did not exist. Until 1976 it was not possible to invest in an index. And it wasn’t until the 1980’s that it was possible to invest in the type of portfolio the author is suggesting. This is not bad per se, but it is a misnomer to think that an investor could have ever experienced the returns suggested by the author had they followed the author’s advice.