Fellow Partners,

A number of you have kindly asked if you could forward these updates to interested parties who share our long-term, patient, focused values. Yes! Please do.

If this letter has been forwarded to you and you would like to discuss further, please reach out to info@phronesisfund.com.

Here is the October update.

Summary

The market is expensive or cheap depending on how you measure. But what really matters is the value we get for what we buy.

Risk is hoping for too much in the future

Patience is our biggest competitive advantage

Investing is the greatest game on earth

Several resources have been added to the partnership portal

Expensive or cheap?

We continue to believe that equities are cheap.

Bill Ackman, Pershing Square Capital, May 2020

This is the second-most overvalued market I have ever seen.

David Tepper, Appaloosa Management, May 2020

A lot has happened since May, but these divergent opinions from two investing legends still adequately summarize the current debate on market valuation.

Who is right?

That depends on your starting point.

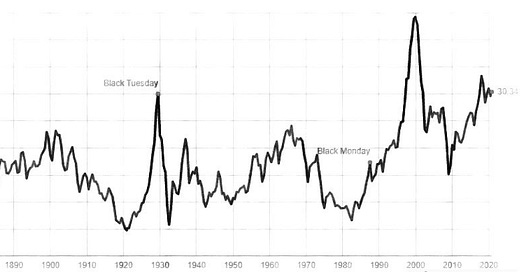

The “market is overvalued” camp tends to compare current market valuations vs. historical valuations and conclude that the market is overvalued vs. history. The Shiller PE ratio is one such metric and clearly we’re on the high-end vs. history [1].

The “market is cheap” camp tends to look at the market in a way that allows us to compare all types of assets — not just stocks. I touched on this briefly in our September Partner Update. Chamath Palihapitiya of Social Capital recently summarized this well here (thanks Andrew for pointing this out!):

If one has money to invest (and the Fed has supplied plenty of it) then they make a risk/reward decision on where to invest it. The option historically considered to be “risk free” is US government bonds. But their returns have been declining for the past 30 years and are now below 1%.

This creates an incentive to look elsewhere. One can compare assets via yields — for example, a market PE ratio of 31 (shown above) is a yield of about 3%. Not great, but well above government bond yields.

This is even more appealing when one considers that bond yields are fixed — one knows upon purchase exactly what they will get paid, and when. By contrast, stocks have the potential to grow in value and/or produce future cash flow. A guaranteed sub-1% return is unappealing vs. a potential 3%+ return, especially for capital that can be patient.

Betting on too much future performance

This partnership does not exist to seek 3% returns (as you know, I am not paid an incentive fee unless I clear a 6% hurdle each year).

What is the risk vs. bonds? Primarily in buying poor businesses, and in overpaying for wonderful businesses.

Poor businesses — as defined by poor business models — can be identified and avoided. One way to look at this is businesses that need a lot to go right to make good money. The example du jour is airlines. Yes, they can be highly profitable, but to do so they need to keep most of their planes mostly full of passengers most of the time. They must pay enormous operating costs (and given their use of debt, large financing costs as well) to keep their planes in flying condition and their operations running. If they can keep their planes mostly full, they make bank. If for any number of reasons they can’t do this, they are highly leveraged with operating and financing costs that can only be partially reduced to offset lower demand.

I clearly remember hearing American Airlines CEO Doug Parker say “I don’t think we’re ever going to lose money again.” in 2017 [2]. I have never owned American Airlines stock, but if I did I would have sold it that day.

By contrast, wonderful businesses (again, as defined by wonderful business models) can be identified and pursued — e.g. Google’s immensely profitable AdWords business — but they are often priced to match.

In our current market, with lots of money seeking yield and investors willing to “pay up” for it, investors are reaching further and further to justify what they buy. This includes evolving the set of valuation metrics used [3], and looking for potential earnings further and further into the future to justify current valuations.

This can be logical. Only a few percent of a firm’s intrinsic value comes from any single year’s earnings. But when stocks purchased today require many years of strong performance into the future to justify their current price, risk adds up.

Paying too much for future performance (or, what are we doing about all this?)

Price is what you pay. Value is what you get.

Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway

Our focus on wonderful businesses has led us to a portfolio of firms with excellent economics and enormous tailwinds — digital payments, gaming, essential infrastructure, top-shelf media, and digital adverting to name a few.

The primary long-term risk to our ability to compound capital over the long-term is in over-paying for these wonderful businesses.

With interest rates near 0%, the valuation of assets returning above 0% can be quite high. But if inflation goes up (and it will, eventually), these forces work in reverse and valuations of the same businesses come down. So our first risk-mitigation step: avoid buying businesses at prices that require the interest rate to stay near 0% to sustain a reasonable valuation. For our evaluations it is useful to assume that the long-term sustainable interest rate is well above its current level and act accordingly.

A related risk is paying a price for businesses that requires perfect execution well into the future. It can be logical and very profitable to pay for businesses that will not make substantial profits for years into the future — especially when they are using returns from current business operations to fund the growth of their business or development of new businesses.

Bezos lays this out very well here (9 minute clip):

But what happens if a business stumbles in its execution? We want to buy businesses at prices that — even if the business stumbles — would still produce good returns on our investment.

So where do we focus?

Wonderful businesses that can experience execution challenges and/or rising inflation while still providing good returns on capital.

Focus on the controllable inputs to your business instead of the outputs; in the long-term you get better results.

Jeff Bezos, Amazon

Imagine a business required to meet every current growth expectation for the next five years and the interest rate must remain near 0% to reasonably justify its current price. Now imagine a business that can miss expectations and handle the inflation rate rising several percentage points and still be valued above its current price.

The first business is Zoom ($ZM) and any number of other businesses in today’s market (wonderful, but expensive). The second business is Berkshire Hathaway ($BRK), Nintendo ($NTDOY) and a few other businesses in today’s market. All are wonderful businesses — but we prefer the company of the later.

Patience is our main competitive advantage

When will the interest rate rise? When will the price of our portfolio companies rise to meet or exceed their intrinsic value?

No one knows.

But that’s the point of our strategy.

Patience is our main competitive advantage.

Those of you whom I worked with during March and April of this year — what turned out to be the bottom of the market (though of course we didn’t know it then) — know how well our ability to deploy calm, patient, focused capital amidst that market environment of panicked and short-term thinking worked out. We quite literally bought dollars for fifty cents. We were only able to do that because we were deploying capital that did not require short-term rationalization by the market. (The market bounced back quickly but no one knew that it would at the time; if they had, those opportunities would not have existed.)

Investing is the greatest game on earth

I am often asked what I pay attention to in the markets. Which data, signals, trends, investors, etc.?

One way of thinking about investing is as one of the world’s most complex, enigmatic problems with infinite and highly variable solutions.

So my answer: everything matters. But not everything matters equally.

Those of you that I’ve discussed process with know that I view capital markets as a complex adaptive system wherein competitive advantages evolve over time.

In the 1940’s one could make a fortune by simply buying companies trading for less than the combined value of their cash and liquidated assets. But others got wise. In the 1980’s one could make a fortune by levering up businesses with debt to juice their equity returns. Then others got wise. In the 1990’s one could make a fortune using complex business valuation variables to determine what was cheap and buying or selling accordingly. Then others got wise. This pattern has repeated over and over, and it will continue.

An unpopular but strongly-held belief: avoid investors that have a dogmatic, highly repeatable process. If their process is repeatable enough and profitable enough, it will be copied, to the detriment of future returns [4].

Perhaps the biggest dogma of the past 5-10 years has been simply buying the market (e.g. an S&P 500 index fund) and leaving it alone. This has absolutely been one of the best performing strategies of the past decade, and, as I’ve said before, a good option for people who would otherwise treat capital markets like casinos. But some forget that the strategy returned exactly 0% in the prior decade. Or that the significant majority of stocks within the index have actually performed poorly, but a few monster performers have more than compensated for the poor performance of the majority.

What’s next? It’s anyone’s guess. But this is why there is no substitute for applying practical wisdom, reasoning from first principles, seeking wonderful businesses at reasonable prices, and playing the long game.

Some are maddened by the complex and enigmatic nature of investing in capital markets.

I think it’s the greatest game on earth.

Updates and reminders

All partner updates and resources are available on our portal. These include the full team that serves the fund, our investment philosophy, and will shortly include a link to on-demand statements. I will provide further details in next month’s update.

As always please feel free to reach out to discuss the above or anything else (details below).

All the best,

John

Founder and Managing Partner

Notes and references

[1] https://www.multpl.com/shiller-pe

[2] https://www.cnbc.com/2017/09/28/american-airlines-i-dont-think-were-ever-going-to-lose-money-again.html

[3]

[4] There are exceptions, of course. A major exception is patient capital willing to ignore the short-term vicissitudes of the market. Most investors aren’t very patient, so patient strategies can repeatedly perform well.