This is the third entry in a 3-part series. Part 1 defines a useful mental model. Part 2 covers the seasons leading up to our current economic realities. Part 3 describes where we may be headed.

Fellow Partners,

As you read this note, I encourage you to keep in mind our mantra of having “the longest view in the market” and our singular focus on the intrinsic value of our businesses years into the future. This means our partnership will only be impacted by any persistent effects of the seasons we are currently experiencing. Anything in the category of “this, too, shall pass” is not of lasting concern to our calculus.

As discussed in Seasons Pt. 2: How We Got Here, an excess of excesses including easy money, maximum globalization, and geopolitical stability led to asset booms. These seasons have turned.

Consumer sentiment is the lowest it has been since 2011, inflation is at levels last seen in the early 1980s, and expectations of economic conditions are at their lowest since we started measuring them in the 1950s. Capital markets are in recession territory. Some areas of the market have pulled back violently. One can feel the glee from news outlets. Fear sells.

Perspective

We must note that this is not the whole story. There are upsides to chaos. And we’ve been here before. Consider Earl Zukerman’s take on the 20th century:

Imagine you were born in the United States in 1900.

On your 14th birthday, World War I starts, and ends on your 18th birthday. 22 million people perish in that war.

Later in the year, a Spanish Flu epidemic hits the planet and runs until your 20th birthday. 50 million people die from it in those two years. Yes, 50 million.

On your 29th birthday, the Great Depression begins. Unemployment hits 25%. World GDP drops 27%. That runs until you are 33. The country nearly collapses along with the world economy.

When you turn 39, World War II starts. You aren’t even over the hill yet. And don’t try to catch your breath.

On your 41st birthday, the United States is fully pulled into World War II. Between your 39th and 45th birthday, 75 million people perish in the war.

At 50, the Korean War starts. 5 million perish.

At 55, the Vietnam War begins and doesn’t end for 20 years. 4 million people perish.

On your 62nd birthday you have the Cuban Missile Crisis, a tipping point in the Cold War. Life on our planet, as we know it, should have ended. Great leaders prevented that from happening.

When you turn 75, the Vietnam War finally ends.

All that, and the lifestyle of the average American by the end of the century was far better than that of the wealthiest American at the start of the century.

Zukerman continues:

Think of everyone on the planet born in 1900. How do you survive all of that?

Perspective is an amazing art, refined as time goes on, and enlightening like you wouldn’t believe. Let’s try to keep things in perspective.

Forthcoming Seasons

If people could predict the timing of economic seasons with certainty they would rapidly become the richest people in the world. That the world’s richest people generally build or inherit their wealth tells us that perfect prediction of seasonal paths is not possible.

However, we can assess present incentives to understand the likely direction of travel of future economic seasons. We cannot know when they will arrive, but we can understand the attributes of their vectors vs. present realities.

Every storm runs out of rain.

Gary Allan

From their current points of monetary contraction, deglobalization, and geopolitical instability, future seasons may hold the following:

The long-term price of money (interest rates) remains low, supporting reasonable valuations for businesses such as those we invest in. Major rich world governments are so indebted that they cannot afford the debt payments that would accrue under programs of sustained high interest rates. While the world’s major central banks are generally raising rates and reducing stimulus to fight inflation, they cannot sustain policies much beyond their modest targets. In the US, the Fed believes the neutral rate is 2-3% (the average 10-year Treasury rate over the past five years was 2.3%). This means the likely long-term price of money is low, which is supportive of longer-term reasonable valuations for businesses like ours that aggressively invest in future profits, provided they can produce healthy free cash flow that limits their short-term dependence on capital markets.

Economic resilience increases, which reduces the uncertainty that reduces asset valuations. The long-run effects of some amount of deglobalization will prove beneficial. We desire economic ties with other nations as these offer the benefits of geopolitical stability and competitive advantages. We also desire a reduction in systemic fragility — nations must have some independence in production factors critical to their success so they can avoid economic dependence that leads to bad policy (e.g., about half of Germany's natural gas coming from Russia) and economic fragility that leads to critical failures (ask Ford about the trucks they couldn’t sell due to semiconductor shortages). We want systemic economic resilience, and some amount deglobalization will support this. This won’t happen overnight, but there’s plenty of evidence of the trend (e.g., the world’s largest semiconductor fab is scheduled to open in 2025 in Columbus, Ohio).

Geopolitical uncertainty declines, which reduces the uncertainty that reduces asset valuations. This variable has the greatest degree of uncertainty as it is controlled by forces far beyond economic incentives. That said, witnessing what can happen — which we are seeing in the war in Ukraine — is an antidote to it happening again soon. We want long-term geopolitical stability, and geopolitical events larger than our day-to-day partisanship are galvanizing forces in that direction.

Inflation

What about inflation?

Core inflation is likely near its peak (core inflation excludes typically volatile food and energy prices). Rising interest rates reduce demand, extremely low consumer sentiment is a leading indicator of people purchasing less in the future, base rate effects are now making inflation growth more difficult, and purchasing habits are reverting to trend making declines easier and easier.

To understand this last point, it helps to appreciate how significantly off-trend consumer habits became during Covid-19 (see chart below). A year ago consumer spending on goods was $500 billion above trend, while services spending was nearly $1 trillion below trend — unsurprising as few were taking holidays but many were upgrading their dwellings.

This contributed to inflation (too much money chasing too few goods) but is now reverting back to trend. Target recently reported a 48% reduction in earnings vs. a year ago, and warned of additional weakness this year because they bought too many goods.

We [expected] the consumer to continue refocusing their spending away from goods and into services…we didn’t anticipate the magnitude of that shift.

Brian Cornell, Target CEO, May 18, 2022

Consumers binged on goods during the pandemic. They are now binging on services. Eventually their behavior will normalize, which will enhance the value of price signals, which will enable supply chains to better match supply with demand. In short, the core inflation game will get easier.

Contrasting with likely core inflation reductions will be continued volatility in overall inflation due to volatility of food and energy prices, which together make up just over 20% of the current inflation calculus.

About 50% of the world’s caloric intake comes from grains. The enormity of global grain output is due to modern fertilizers:

Between 1800 and 2020, we reduced the labor needed to produce a kilogram of grain by more than 98%—and we reduced the share of the country’s population engaged in agriculture by the same large margin.

…

In 2020, nearly 4 billion people would not have been alive without synthetic ammonia…. the Haber-Bosch synthesis of ammonia [is] perhaps the most momentous technical advance in history.

Vaclav Smil, How the World Really Works

There are various forms of fertilizer and fertilizer inputs. The present picture is bleak. China, the world’s largest exporter of phosphate, stopped exports last year. Russia, a major producer of potash, has been unable to export it because the government turned Black Sea ports into a war zone and ships won’t go there. Russia was also the largest exporter of components for nitrogen-based fertilizer, and Europe has stopped producing nitrogen fertilizer due to the high cost of natural gas, which is about seven times higher vs. US prices (more here if interested).

Grain production relies on timing and effectiveness of planting and harvest seasons, and there are not rapid ways to bring new fertilizer production online. Altogether this means we will have a global food shortage starting later this year, likely at the cost of human lives in the global south and continued inflation in food prices.

There is a somewhat similar story for global energy needs.

We should also expect continued dramatic swings in the prices of food and energy. As 20%+ of the inflation calculus, these swings will continue to impact overall inflation for the foreseeable future.

A Return to Quality

What do these seasons mean for our investments?

We own some wonderful businesses. As they weather these seasons they’ll get even better.

Bad companies are destroyed by crisis, good companies survive them, great companies are improved by them.

Andy Grove, former CEO of Intel

Difficult economic circumstances create some predictable realities.

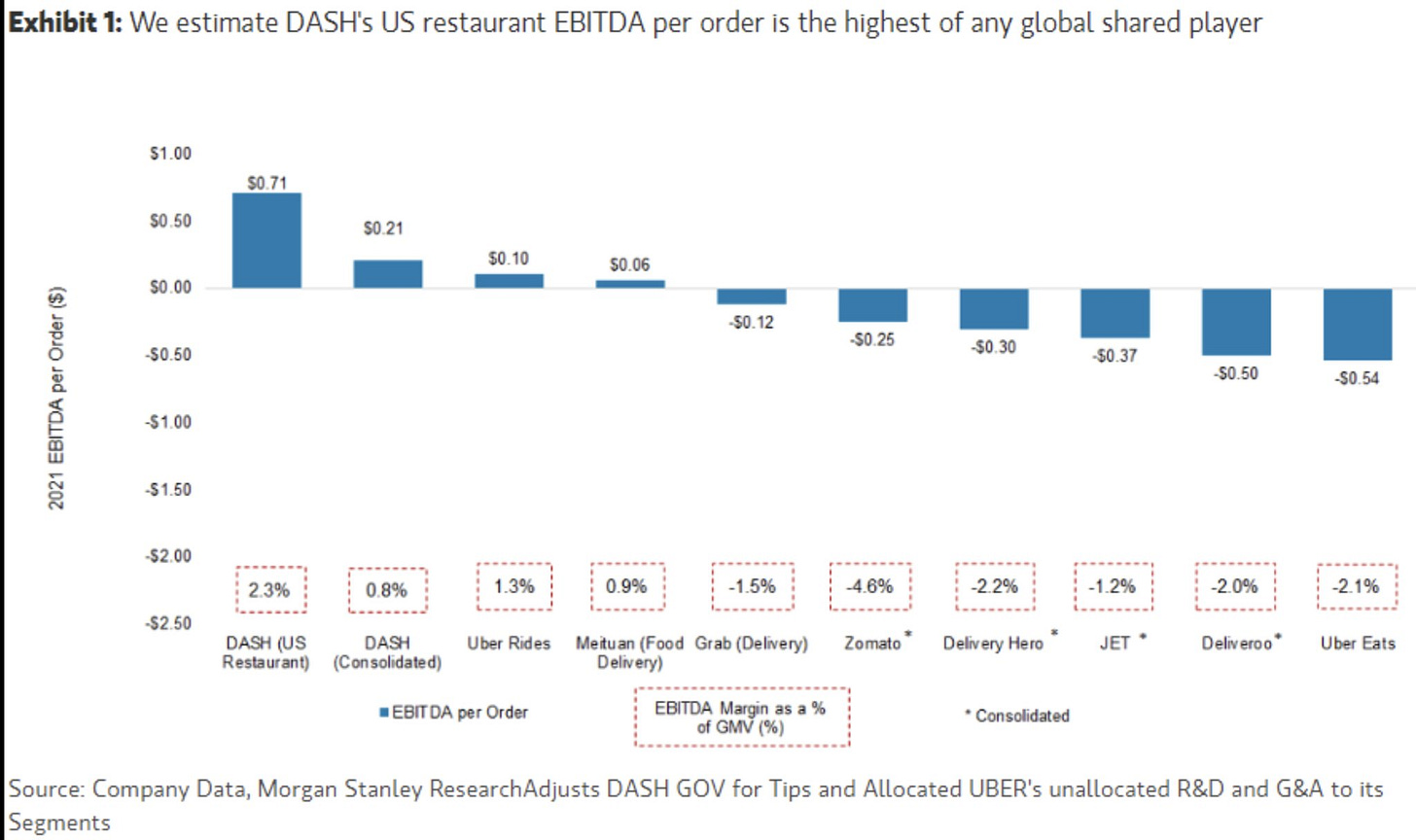

A notable trend in the past decade was the absence of bankruptcies — cheap money delayed the inevitable culling of unsustainable businesses and business practices. We will now see much more focus on free cash flow and unit-level profitability (e.g., the chart below). Bad businesses will go bust, to the long-term benefit of better businesses that can take their market share.

An important component of this reality will be a more reasonable landscape in the war for talent. Data continues to suggest there are about two job openings for every person seeking employment. A strong job market is a wonderful thing, but in extremis it can force businesses to overpay for talent which increases operational risk. A difficult economic environment will result in improved job price discovery — that is, a more balanced equation between employee willingness to work and employer willingness to pay. This will reduce employment fragility for the best businesses and the best employees, to the benefit of both.

Deflation

As we recently discussed the inflation debate can be framed as demographics and technology vs. money for nothing. These variables are more important than ever:

The shrinking rich world. Declining populations reduce aggregate demand which is a deflationary force. This will happen slowly, though it is also a compelling reason to be invested in areas that will benefit as demographic weight and household wealth shifts to younger generations. As younger generations grow wealthier and more influential, their preferences become more pronounced in the market, creating a natural secular tailwind for businesses that serve their preferences (examples include expansion of e-commerce, digitization of financial services, and the growth of gaming).

The relentless march of technology. The rate of change of the rate of change (say that five times fast…) is accelerating — the “game” has sped up. Digital bits move faster and more freely than physical atoms. As digital bits become larger and larger components of overall economy, we should expect larger and faster degrees of change in competitive landscape, solutions, and transitions — especially those that serve things that never change (e.g., the desire for better/faster/cheaper products and services).

The secular curve of technology solving big problems has never been steeper, and the cycles that overlay that secular curve are not suspended. It is happening in record pace.

Brad Gerstner, Founder & CEO, Altimeter Capital

I recently rode my favorite attraction: Walt Disney’s Carousel of Progress. Originally opened at the 1964 World’s Fair, it has been through a number of upgrades, most recently in 1993. Here’s what 1993 Disney thought a futuristic home would contain in the year 2000: programmable voice controls, simple VR gaming, car phones, laser discs, and hi-def TV.

Every single one of those items is not only widely available today, but also widely affordable, and several orders of magnitude better than imagined not too long ago (e.g., smartphones vs. car phones, self-programming voice assistants, and streaming media).

Playing the Longest Game

Cycles are neither good nor bad; they are natural. Peak euphoria provides the opportunity for the world to dream about the future. Rock-bottom despair forces practicality and clarity. When things are good, they're never as good as they seem; when things are bad, they're never as bad as they seem…. Zooming out, cycles can be reframed as volatile periods around a relatively consistent adoption curve.

Fred Ehrsam

Thinking in seasons helps us to look ahead, especially in times of stress. Our investments will fare better in some seasons and worse in others. What will matter through those seasons is whether we are correct in our assessment of the quality and durability of our investments, whether we buy our investments well, whether we use seasonality to our advantage (e.g., buying when there’s blood in the streets), and holding our investments to the realization of their long-term intrinsic value.

To these ends we often ask ourselves these questions:

Do our investments offer wonderful value propositions and have substantial barriers to those propositions being competed away by others?

Are we buying our investments at reasonable discounts to their long-term intrinsic values given reasonable levels of interest rates, globalization, and geopolitical stability?

Will our investments benefit from things that will never change (e.g., the desire for better/faster/cheaper products and services) — as opposed to things that do change (e.g., tastes and fashions)?

Will our investments benefit from major secular tailwinds including shifting demographic weight and household wealth?

When we can answer “yes” to these questions, we accept that the ride to the finish can be bumpy, but the finish is what we care about.

From there, we are cognizant of our present seasons and how they can advantage our multi-season ownership of wonderful businesses.

And then, we ignore the noise.

All the best,

John

Founder and Managing Partner