Fellow Partners,

In a world of infinite content the price of attention ought to go up, and up, and up.

Why?

Let’s go back 10,000 years. Marketing — to the extent it existed — was simply a way of learning where to find what one needed i.e. “Where is the baker?”

Over subsequent years the growth of trade saw the creation of and access to more and more goods and services. Marketing evolved into “What is available?”

Today there are more goods and services available than species on the earth — tens of billions of things to choose from.1 Marketing has evolved into “What do I want?”

The only absolutely scarce item in this kind of economy is attention.2

More and different things will be created. And the world’s population is growing a bit. But at this very moment in time there are about eight billion people alive, and therefore about eight billion minutes of attention currently in progress.

That’s it.

No amount of better/faster/cheaper can create more attention. Attention is the only truly scarce asset.

Attention is the one thing sellers of goods and services must have in sufficient supply in order to survive. Without it, they’re dead in the water.

So, is the price of attention going up?

Attention is a moral act. Attention changes the world. If you attend to it in a certain way you see certain things. If you attend to it in another way you see quite different things. Attention helps to bring into existence the experiential world, which is the only world that we can ever know.

Iain McGilchrist

Waste

One way to answer this question is to assess the proportion of advertising spend as a percentage of total GDP. A rising figure would suggest the world in aggregate is spending more buying attention.

Over the past three decades we’ve actually seen a slight decline in this figure. This may be surprising at first glance.

Cue John Wanamaker:

Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don’t know which half.

Think of the endless TV commercials for cars you’ll never buy. What a waste.

Value accrues where attention pools, and the attention well for generic commercials is shallow.

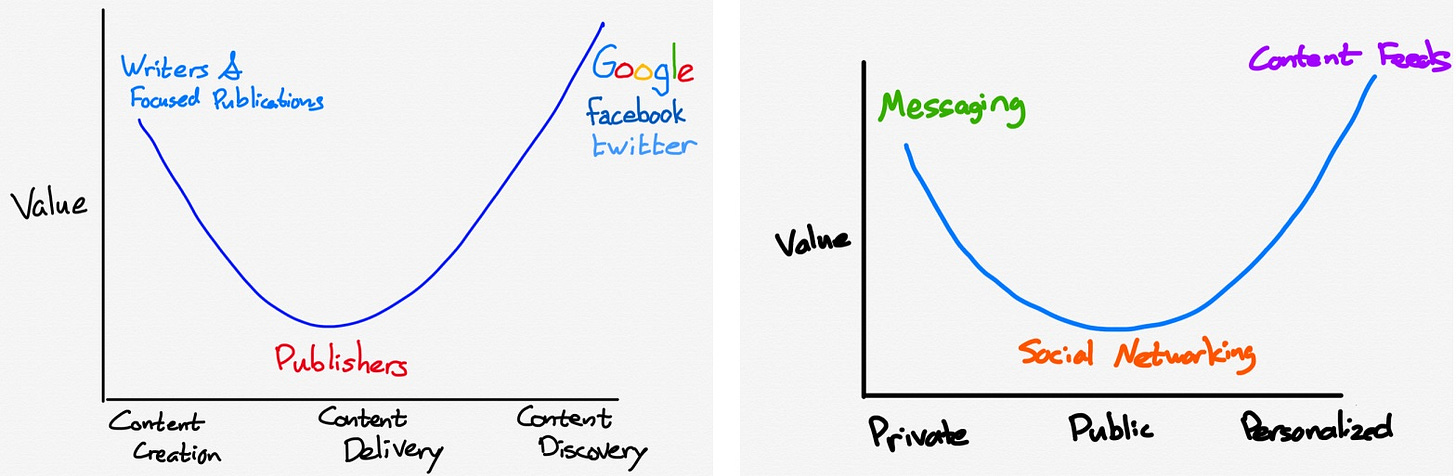

What do you really pay attention to? Content you seek out, and content personalized for you.

So, is the price of attention declining, or are we just getting more efficient at finding it?

Here’s the same chart of global ad spend as a percentage of GDP, overlaid with the proportion of ad spend allocated to three dominant digital advertisers.

A reasonable interpretation is that advertising got better faster than it got more expensive.

Unsurprisingly, the global advertising market is expected to grow in excess of global GDP over the next decade.

Number go up

The dramatic shift to digital-native advertising suggests attention is increasingly being priced by digital advertisers.

So, is the price of attention going up?

Search still comprises the majority of digital advertising, so one way we could answer this question is to ask if the value per point of search market share has gone up?

Over the past five years it has roughly tripled.

Another way we could assess the price of attention is to ask whether the price-per-user of those who monetize attention is going up?

We can do so by using a traditional metric such as price / earnings, and swapping “earnings” with a proxy for attention.

Meta (Facebook) has the largest single pool of daily active users (over three billion), and we can see that the price per user has roughly doubled over the past five years.

There are numerous other ways we could poke at this.

In a world of agents and bots, the value of “known humans” ought to rise. Reddit’s dramatic rise in valuation during the age of A.I. is some evidence of this. The rise in value per active platform user at Uber is more evidence.

The specific price of attention will jump around. But the trend is clear, and passes our first-principles reasoning at the start of this essay as well as a priori reasoning from e.g. aggregation theory.

We have enough to act on.

What do we do about it?

First, we should expect the price of attention to continue to rise. In a world of rising noise — with far more products, services, bots, and content than humans to consume them — we should expect the price of attention to continue to rise, and only be limited by the lowest sustainable margins of those that need to purchase it. To rephrase Bezos:

Your lack of attention is my opportunity.

Second, we should mark up the value of the attention we already have. It is obvious that one’s existing customers are their most valuable customers. But have you increased the value you ascribe to them? The data above suggests one’s cost to re-acquire them has gone up 2-3x over the past five years.

Third, we should expect the value of curation to rise. In a world of infinite options, sometimes the only way to find a good solution is to search in a limited field. Using the internet to find a good restaurant in a city is much harder than asking a trusted friend who lives there. So, too, with just about everything. Curators will increasingly direct attention.

Fourth, we should expect content quality to go up. That is counter intuitive. But think about the search function for enduring content. Out of billions of paintings, books, songs, and movies we have found a precious few pieces of enduring content. The rate-limiter to these works — training, materials, assistance, and so forth — are plummeting in cost. This means the cost of creating “noise” is going down, but more noise also increases the odds that some of it contains real signal. We used to say, given enough time, that a monkey with a typewriter would eventually produce Shakespeare. Since we can compress creation, this is now possible in a reasonable amount of time. More noise gives more potential for signal. The challenge, of course, remains finding it.

Finally, the value of enduring content will rise. As the cost to create “noise” approaches zero — think Generative A.I. publishing infinite content — the value of enduring content ought to rise. This is a version of the curation point, but for the content itself. It will become even more useful to directly seek out and consume enduring content because finding new enduring content will become increasingly difficult. This is the Lindy effect at work.

In closing

It is an honor to serve you. As always, please reach out any time.

Thank you to CB, Lucy, Drex, Brian, and Ahmed for feedback on early drafts!

All the best,

John

Founder and Managing Partner

See Eric Beinhocker The Origin of Wealth.

We define attention as the direction of time and energy.

Interesting essay. How do you incorporate your thesis into your investment philosophy and practice?

Since I long to write marketing copy that captivates again and rewards attention, I support your hypothesis. As someone who considers herself a curator of creative talent, I am preparing for just such a future.