Fellow Partners,

We invest in two things and only two things: cash flows and insurance.

The overwhelming majority of the investment industry has divided and sub-divided investing into a thousand tiny pieces called asset classes, sub-classes, attributes and factors, mined mountains of historical data, suggested that this creates a roadmap for the future, and claimed a need for master mathematicians to put the pieces back together for your benefit.

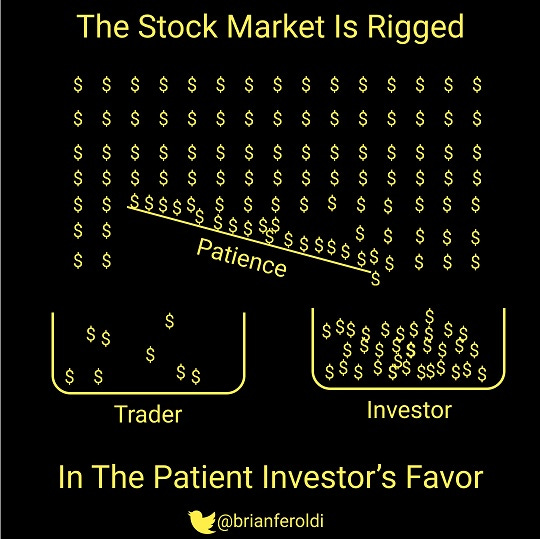

Because we choose to play a long-term game and only a long-term game, we get to ignore nearly all of the history-predicts-the-future complexities that have sold well for the past few decades.

Because we choose to play a long-term game and only a long-term game, we can seek to maximize long-term returns and only seek to maximize long-term returns. This isn't a popularity contest. This isn't asset squatting. This isn't pursuit of short-term bragging rights.

We invest in two things and only two things: cash flows and insurance.

Cash flows

We primarily seek to invest in something of value. In the long-run we always end up back at Economics 101: goods and services people are willing to pay for. In the long-run everything is a discounted cash flow model — which merely means we must estimate how much cash a potential investment is likely to produce, discount future cash flows back to the present, and seek to buy substantially more cash in the future with the cash we have today.

Because we choose to play a long-term game and only a long-term game, we focus our efforts on understanding probabilities of gain times magnitude of gain, less probabilities of loss times magnitude of loss. What we deem as the best opportunities end up in our portfolio.

Because we choose to play a long-term game and only a long-term game, we do not focus on a thousand tiny pieces, getting exposure to everything, or using history to predict the future. We invest in the areas we do because they are areas likely to produce the best opportunities that we are able to understand.

This is why we discuss the philosophies and behaviors we seek to apply in this partnership: long-biased; applied practical wisdom; first principles reasoning; patience. That's it.

You will not hear us discuss style boxes or find us painting ourselves into corners. We are looking to catch the best fish that we know how to catch. And fish swim around.

Insurance

Maximized returns are worthless if one blows up in their pursuit. This is regrettably common and often an argument against portfolio concentration. It's a good one, too, if applied thoughtfully.

Because we choose to play a long-term game and only a long-term game, we get to ignore nearly all of the insure-against-short-term-losses complexities that have sold well for the past few decades. When we think about insurance, we think about our ability to cross a hypothetical finish line decades from now despite substantial changes and challenges that we know we will face.

We don't seek to time the market. We do seek to figure out more substantive barriers to crossing the finish line decades from now. Our patience is the bedrock of this ability, as it allows us to ignore market prices at all times unless buying or selling is to our advantage.

We also think about deep structural factors: substantial inflation or deflation (both poorly understood and difficult to control); a decline in the global role of the U.S. dollar (seigniorage is a powerful advantage; those without it root against it); structural impairments to global reserve currencies such as excessive debasement.

Finally, we think not just about change but rates of change. Change is accelerating, but the rate of change is also accelerating. Thanks primarily to the deep currents of digitization, globalization and inexpensive capital, the speed with which ideas can move from concept to execution to scale to dominance is fast and getting faster — firms are reaching billion-dollar figures faster than ever.

Now consider that the data above is from 2015 and the driving trends behind it have all accelerated — substantially in some cases.

We are firmly in a world of "megas and minnows" (thanks to Josh Wolfe for this concept) — where success comes via extreme scale (winner-takes-most) or defensible niche (winner-takes-community). In this context, having the humility, hardiness and wherewithal to invest not just in what is working well today but what could compete it away tomorrow is important. To borrow from Hemingway, these disruptions are likely to happen "gradually, then suddenly." We position ourselves accordingly.

The lessons of history

None of the above is to suggest that history is irrelevant. We must learn its lessons — and realize that its lessons are largely about the immutability of human behavior.

The biggest takeaway from history is that the characters change but their behaviors don’t. Markets change, but greed and fear never do. Industries change, but ambition and complacency don’t. Laws change, but the tribal instincts of politics don’t.

Morgan Housel

However, we must also be careful to avoid the seductive belief that businesses’ past equations are a roadmap to the future. It is supreme irony that human behavior desperately seeks certainty, does so through studying history, and misses the point that history is predominantly the study of change.

All history is the study of what’s changed, but it’s often used as a guide to the future. The irony is overlooked because the idea that if we gather enough data and read enough books we’ll acquire a map of the future is so seductive – it’s so simple, and makes you feel great.

That will never change.

Morgan Housel

Closing thoughts

Cash flows and insurance interplay. While most forms of insurance typically have a net-cost, some forms can be positive carry hedges or yield profits over longer time horizons. While we can't know with certainty which forms of insurance will have these long-term attributes, we can focus our efforts positioning within good trade-offs.

For example, in banking near-term cash flows are dominated by the world's major banks that have regulatory capture. These are attractive cash flows, and so they are being eroded by newer players who are un-bundling banking into more specialized services, and in some cases re-bundling them back into more modern institutions.

Further out still, some forms of competition are emerging that enable decentralized, automated borrowing and lending capabilities that may erode cash flows from even the newer players nipping at the heels of today's major banks.

We don’t have a crystal ball about businesses, we don’t expect history to give us one, and we're not blindly guessing. But we are positioning ourselves such that we'll be just fine however much change does (or does not) occur, at whatever the pace may be.

All the best,

John

Founder and Managing Partner