Fellow Partners,

We have had internal processes — “know-how” — since the dawn of humanity. An enormous amount is baked into one's body. It is incredible that these capabilities can lie dormant for long periods of time, and “wake up” when needed (e.g. the blood coagulation cascade that activates when one starts bleeding).

We have had operational processes since we learned how to hunt, fish, build fires, make basic tools, and other solo efforts.

We have had managerial processes since we learned how to trade, hunt and farm in groups, and other efforts that require people working together.

We have had governance processes since we began coordinating human activity for statehood, military operations, and other efforts that affect many people.

And we have had industrial processes since we began dramatically scaling all of these processes up a few hundred years ago.

Software eats the world

The Enlightenment laid the groundwork for the software industry. Beginning with the Enlightenment, our ways of knowing things became hyper-focused on hyper-rationalism. Over time, the scientific method became our dominant epistemology1. This called for data. Data called for computation. And as the scale of data grew (alongside our ambitions), computation called for mechanization, which led to digitization and software.

Babbage's analytical engine gave us hope, and a start. Alan Turing and others moved us along. Once we had punch cards and mainframes in the 1960s, the stage was set. We believed data was the primary means to capital-T Truth, and industrial scale computation was the means to get it.

Over time, software ate the world.

The medium is the message

Add software to hardware and (cue Emeril) BAM! — modern machines.

Machines are wonderful. Most commercial success owes a debt to them. (Incidentally, most personal success does not). But we would be wise to consider some unspoken assumptions in the mechanization of the world.

For avoidance of doubt: The “mechanization of the world” is mechanization via both software and hardware. All software runs on hardware, and today most hardware is controlled by software. Modern machines are anything with a chip: computers, kitchen appliances, calculators, cloud services, phones, headphones, HVAC units, elevators, cars, robots, etc.

Machines are a step towards an end solution. Machines organize and optimize food production, sales and logistics so that we may eat. Machines design, print, and ship books so that we may read. Machines empower us to interact with great libraries of knowledge so that we may learn. Machines make it possible to communicate over great distances so that we may connect.

What lies behind these things are human desires: to eat, to read, to learn, to connect. Machines merely amplify the decisions to do so.

Machines help make things better, faster, cheaper. More for less. More for more people. It is incredible that the richest and poorest people in the world now own many of the same things. That wasn't true for most of human history.

But all of this is in service of humans and how we want to live. Machines are a stepping stone to get to an end in a way that wonderful food, verse, learning, and genuine relationships, are not.

Humans engage in the good, true, and beautiful for its own sake. For machines, these things can only be understood as utility.

One example: machines have been better chess players than humans for several decades. Yet I don’t know anyone watching machine vs. machine chess matches. Magnus Carlsen still matters. And for all his flaws vs. machines, in the chess world he still matters a lot.

I, Robot

It is clear that we — humans — select our pursuits and use machines in pursuing them.

Consider the history of man and machine through the lens of cotton (or any crop).

Cotton was initially planted, grown, and picked by hand, after which cotton fibers were manually separated from their seeds. The fastest we could move was the speed of the slowest humans in the process.

Then we added the plow so we could plant more, faster. Then we added the cotton gin so machines could separate the cotton fibers from their seeds. Then we added the cotton picker so machines could pick the cotton. Then we automated the spinning of cotton into thread. Then we automated the weaving of thread into cloth.

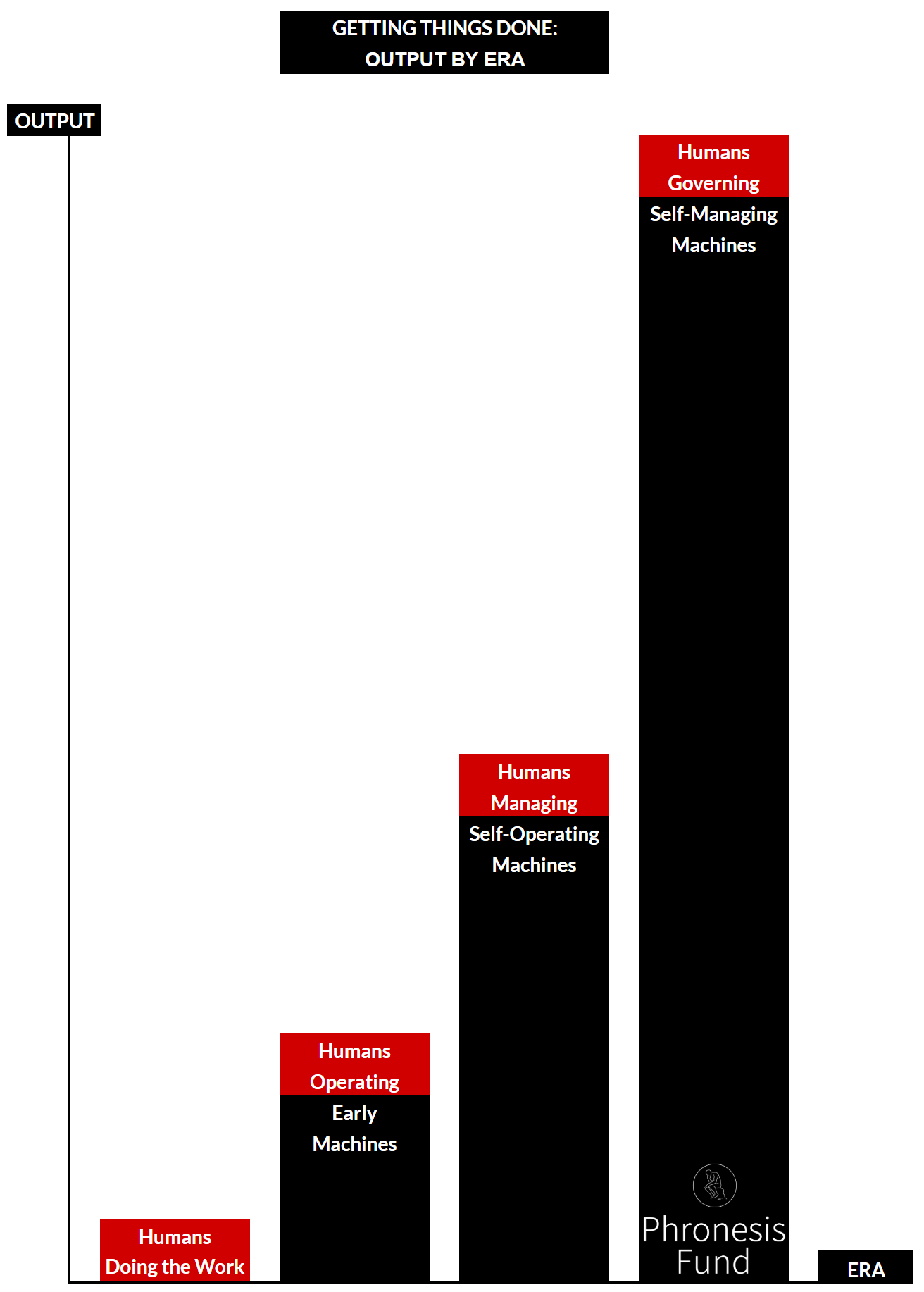

What began as “humans do the work” evolved to “humans operating machines”. Today we are much closer to “humans managing self-operating machines”, and we are peering at the dawn of self-managing machines.

The point: creation and collaboration with machines, at its core, has always been a very human endeavor to pursue the ends we select and amplify the decisions we make along the way. And — era by era — machines have increasingly become the industrial scalers of those decisions.

In practice

From this vantage point we can start to glimpse the future.

What does this mean, practically?

Machines that create work for humans will lose to machines that complete work for humans. If training is required, the machine won’t survive. So, too, for most machines with substantial installation, customization, or support burdens, and the associated labor.

Work that compensates for the frustrations of non-intuitive design — including the design function itself — will erode. This is any task that exists to translate human intent into machine instruction. Some call this “human middleware” or “human APIs” — operations only necessary when machines cannot self-operate while the humans manage and govern.

Value will migrate from those who can operate machines to those who can define the purpose of machines. Humans select their pursuits and use machines in pursuing them. “What ought we do?” is a more profound and difficult question than “What are we doing?” Those who can adequately answer the “ought” questions will define the pursuits that machines will amplify.

The best human work is the work that only humans can do: work that is relational, and work that is creative. Wonderful relationships are their own reward. So is friendly service. And wise stewardship. These things are beyond the domain of machines. Creativity, too, has its own rewards. Machines can mimic and remix — incredibly well at this point. But they cannot optimize for things that defy optimization.

Taste matters, and will matter more and more. The work that only humans can do ties directly to deep, philosophical questions which compress down to “how do we want to live?” Historically excellence was exceptional. It will increasingly be expected. Those well-calibrated on what this means and how to deliver it will become more-and-more sought after.

Everything speeds up. Time has always been one of our most valuable assets. As the rate of change increases, economy of time will matter more and more, and the winners will be those able to combine rapid adaptation with timeless wisdom. For a glimpse of the speed:

A 20% annual improvement rate over 10 years improves the total by 6x.

Adding a second 20% annual improvement rate improves the total by 100x.

Adding a third 20% annual improvement rate improves the total by 30,000x.

Over the past 10 years, we have improved our ability to convert energy into intelligence (LLM tokens) by a factor of 100,000x.

Everything that is not connection, creation, or curation (and their required ingredients e.g. character, wisdom, judgement) will recede into the background. This includes most modern machines. In reality this has already happened. When is the last time you considered the software running your microwave? But it will become much more stark as we realize most machine categories shouldn’t be categories at all. Just as smartphones rapidly made obsolete most alarm clocks, calculators, flashlights, stopwatches, timers, portable media players, cameras, camcorders, GPS devices, physical maps, address books, voice recorders, printed photos, tickets, boarding passes, scanners, and so forth, so too large language models (in various configurations) will make obsolete many specialized categories of knowledge work.

The Wizards of Oz

Where does this all go?

The Star Trek universe offers an interesting case study. In it, humans learned how to solve most material needs. Once basic human needs were met en masse, some humans — and all the stars of the series — went off to look for strange new worlds. How is that for a statement of purpose?

Space: the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise. Its continuing mission: to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no one has gone before.

Opening monologue for the first two Star Trek series

We have seen this in the human record. Mountaineer George Mallory attempted to climb Mount Everest “because it is there.” The first person known to succeed (Edmund Hillary) echoed the sentiment.

John F. Kennedy’s famous speech on going to the moon continued in this spirit:

We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win.

Closer to home, consider common advice from elders. Consider what those facing death focus on. Consider what survivors see as important. Consider the world through the eyes of children. Consider the role that art often plays in pointing to the eternal.

I am not suggesting that humans won’t task machines with pursuing terrible ends. (And let’s debate the probability of Skynet another time.)

I am suggesting that the gravity well of human values is more focused on amplifying humans than amplifying machines.

And for all the joys found pursuing great, big, beautiful tomorrows, abstract ideas of progress do not get much attention from one’s death bed. Faith, hope, and love do.

In closing

Machines are not the final form factor. They are merely amplifiers of the ends that we pursue and the decisions we make along the way. That notion should raise our agency, ambitions, and humility.

Thank you as always for the opportunity to compound trust with you.

It is an honor to serve you.

Thank you to Brian for feedback on early drafts!

All the best,

John

Founder and Managing Partner

Defined as “how we know what we know.”