This is the second entry in our Power Laws in Public Markets series.

Part 1 argues that the world is ruled by power laws, not averages.

This essay argues that economy of time is the primary force behind power laws.

Part 3 offers a framework for operating in a world ruled by power laws.

Fellow Partners,

Most humans never witnessed a substantial invention.

The Stone Age lasted many thousands of years. The Bronze Age was about 2,000 years. The overlapping Iron & Classical Ages were about 1,500. The Middle Ages about 1,000. It wasn’t until the Renaissance that our invention cycle — the time required for a major invention — started to plummet. 300 years of the Renaissance. Two centuries of industrial revolutions. Less than a century in the Information Age. And now the sun is rising on the Age of A.I., with the Quantum Age over the horizon.

The invention cycle is a power law1.

In much the same way, for most of human history 50% of children died and those that didn’t rarely made it past 30 years old. It is only in the past few hundred years that our life expectancy started rising — and fast. Today 96% of children born survive childhood2, and life expectancy is now three times higher than it was for most of human history3.

Human survival is a power law.

While the invention cycle was plummeting, human survival was exploding. Slowly, then suddenly, the invention cycle power law and the human survival power law collided.

Humanity found a new gear.

We recently established that Power Laws Rule the World.

We now assert that economy of time is the primary force behind power laws4.

Economy of time

Because most humans never witnessed the impacts of a substantial invention, most humans learned that more hours worked led to more output. Production was a function of time spent. Sure, you could work a little faster and make a little more. But the fundamental rate-limiter of production was time. Most of our world still acts this way. But it is no longer true.

Any time you have outliers whose success multiplies success, you switch from the domain of the normal distribution to the land ruled by the power law — from a world in which things vary slightly to one of extreme contrasts. And once you cross that perilous frontier, you better begin to think differently.

Sebastian Mallaby, The Power Law

I recently spent time with a group of investors committed to learning from each other. We flew in from around the world. Travel, safety, comfort and connection were nearly effortless. The result was that we could spend 100% of our energy learning from each other. The sum of human knowledge was on the smartphones in our pockets. The sum of our collective wisdom was being shared in discussion. I learned more in a couple of days than I typically do in a couple of weeks.

Value creation is compressing.

This group spent a morning with the leadership of an insurance firm. A fascinating theme emerged in our discussions: their obsession with time. For example, they provide policy quotes to brokers substantially faster than their c. 75 competitors ("in by 2pm, out by 5pm" as one leader put it). So while they pay the lowest broker commissions in their industry, brokers can make more money using their services vs. competitors because they can write more policies in the same amount of time. Another example: they wrote and re-wrote their IT authentication system to reduce the time it takes employees to login from c. three seconds down to a few milliseconds. This saves each employee a few seconds or minutes each day. But it adds up over time.

These are modest examples, but they are being amplified on an ever-growing scale.

In the past twenty years the number of employees in S&P 500 companies has doubled. The number of firms with more than 100,000 employees also doubled, as did the number of firms with more than 10,000 employees. While Wal-Mart grew from 1.4m to 2.1m employees, Accenture 10x'd from 75,000 to 750,000 employees and Amazon 200x'd from 8,000 to 1.5m employees.

In market economies, when economy of time improves within organizations the benefits ripple outwards to millions of customers — think of Wal-Mart pursuing lower prices, Accenture globalizing workforces, and Amazon pioneering unlimited compute power for millions of startups through AWS. Those customers in turn have more resources to serve their customers. On and on it goes.

When economy of time improves, the world grows richer.

Value creation is compounding.

The accelerating skill & tool cycle is amplifying economy of time

Scale is important, but it isn't most of the story.

Even at scale, economy of time is rate-limited by the productivity of the work being delivered. The main story is what has happened since we have begun dramatically improving our skills and tools.

We invent new tools, and then the tools change us.

Jeff Bezos

When the invention cycle and human survival power laws collided, humans began to witness new inventions in their lifetimes. For the first time in the history of our species the idea that we could learn and use a set of skills and tools for the rest of our lives began to break. The idea that we could not just work harder but also improve how we work grew in our thinking.

This produced incredible results. Most recently, in the past century the average work week and the proportion of income required for necessities were both cut in half. The concept of retirement was invented. And the proportion of the global population living in extreme poverty went from 85% to 9%.

Value creation is compressing.

Improving how we work required learning to work on the work — the people, information, capital, processes, and so on that produce the end result5. This led to substantial improvements in skills and tools. Production was still a function of time spent, but now it was also a function of how well we spent the time.

The incredible miracle of the common pencil is a wonderful example.

Value creation is compounding.

Economy of time is amplifying individuals

Work productivity and the skills and tools that increase it ultimately amplify the creations of the individuals delivering the work.

For most of human history each person was born, collected knowledge, processed it, and stored it, to be called upon when needed. A tiny fraction of this was taught to younger generations and may have ended up in a paper or book, but for the most part most of each person’s cognitive progress died with them.

Only recently have we begun to overcome the limitations of the single individual for the combined tasks information collection, processing, storage, and recall.

Ed Thorpe’s discovery that Blackjack players can beat the casino is a prime example:

The work I faced in 1959 [was] four hundred million man-years of calculations, with a resulting railroad car full of strategy tables, enough to fill a Rolodex five miles long.

…even though I introduced shortcuts and efficiencies and was very fast, I was making little progress. My hand calculations were going to take hundreds, perhaps thousands of years.

…at this point I learned that MIT had an IBM 704 computer and, being a faculty member, I could use it. Using a book from the computer center, I taught myself to program the machine in its language, FORTRAN.

Weeks passed, then months, as I completed one part [of the computer program] after another. Finally, in early 1960, I put them together and submitted the complete program.

The first results indicated that…when you played as perfectly as possible, the game was virtually even for anyone. It wouldn’t take much in the way of card counting to give the player an edge!

Ed Thorpe, A Man for All Markets

The age of cognitive leverage had arrived.

Value creation is compressing.

How did we get here?

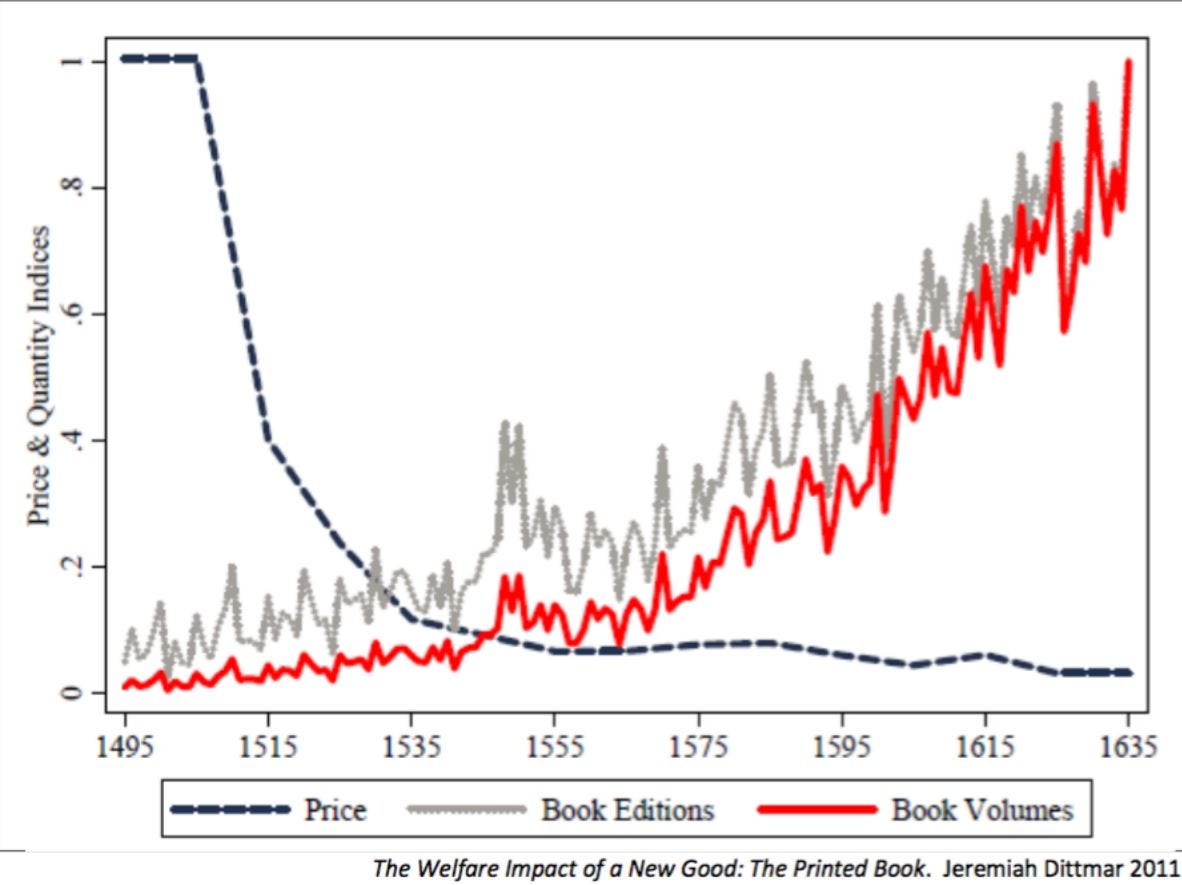

Written text (c. 3400 BC) taught us the value of documenting knowledge. The Library of Alexandria (c. 200 BC) and others like it taught us the value of making written knowledge accessible to wider and future audiences. The moveable type press (c. 1500 AD) supercharged the number of pages per hour a person could produce and thereby the amount, accessibility, and affordability of documented knowledge in the world.

The abacus and, eventually, Babbage’s analytical engine (c. 1800 AD) taught us that work is a function of knowledge, processing, storage, and recall — and that the ability to increase each component can lead to dramatic increases in total output.

These advances helped us learn that technologies are inherently modular (e.g. microchips), with modules assembled into various architectures (e.g. computers). Innovations in modules enable new architectures, and innovations in architectures (e.g. the PC revolution) tend to have the big, catalyzing, ripple effects6,7.

The Information Age ushered in an ever-present state of augmenting and amplifying the capabilities of the human mind.

Our growing ability to create permanent databases, process them with increasing speed and agility, and store and query the results has empowered us to massively augment our intelligence and create the stunning increases in size, complexity, productivity and, ultimately, amplification of human capabilities8.

Value creation is compounding.

What do we do about it?

What does this mean?

The scarcest asset of all is time. The people, products, and organizations that have the greatest impact on economy of time have the greatest potential to produce power law outcomes.

In the final entry of this series we will explore a framework for operating in a world ruled by power laws.

Thank you to CB, Drex, and Brian for comments on early drafts!

All the best,

John

Founder and Managing Partner

A power law relationship is a scaling law in which small changes in one variable result in significant, non-linear changes in another variable. Common examples include the Pareto Principle, the sizes of cities, the magnitude of natural disasters, the distribution of website popularity, and the number of hours streamed per show on Netflix (or any other similar service).

https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality-in-the-past

https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy

By extension, nearly all the forces that move the world occur when power laws collide. That's a big statement, and while we won’t argue every aspect of it in this essay, we stand by it.

Little surprise, by the way, that management consulting, private equity, venture capital, and related work-on-the-work industries were all invented around the same time.

Note here an abundance of power law collisions — massively increasing compute power, massively decreasing chip size, and massively growing computer adoption colliding to accelerate productivity.

Eric Beinhocker’s excellent The Origin of Wealth covers this in detail. See Chapter Eight: Emergence, The Puzzle of Patterns.