Fellow Partners,

For those who are curious, there has always been too much to figure out.

Charlie Munger suggested that Ben Franklin may have been the last human to understand much of what humanity had learned. That was 235 years ago.

For investors, there is enormous complexity across industries. The Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS) suggests we have 11 sectors that can be broken down into 25 industry groups, 74 industries, and 163 sub-industries.

All that before we analyze companies and the people that run them. All that before we get into considerations about how we know what we know and how certain we can be about any of it.

We are as gods

The Enlightenment brought with it a new religion: in reason we trust. If only we could gather enough data and ram it through the scientific process, all would be revealed. Many still believe this.

Yet, zooming out, we see a different story. Newton gave us the laws of motion, and with them we learned to explain much. But we took it too far. We thought we could use them to explain everything. We became our own gods.

We were humbled when we discovered electromagnetism. Newton's laws had limits there. But eventually Maxwell gave us the equations, and we returned to playing gods. We were humbled again when time confused us. But then Einstein set us straight.

Since the dawn of humanity, we have oscillated between being humbled and being our own gods. Reason is just the latest iteration.

Weather confounded us — and still does. And yet through this we learned of complexity — that small changes in starting conditions (e.g. the butterfly effect) combined with feedback loops create unpredictable, emergent outcomes.

Reason hates that. Emergence is beyond its reach. But this is why Moneyball and The Process worked, and also didn't work. We are not the product of mechanical process, and we don't want to be. Mr. Rogers was much closer to reality than the fathers of scientific management.

In practical terms, this means that any time we are dealing with complex adaptive systems — which is pretty much any person, company, government, or institution (and nature, and the cosmos…) — we should expect the future to be unknowable and unpredictable.

Is this true?

Here's a thought experiment I consider almost daily: with today's financial instruments, if one could predict outcomes with very high fidelity, they could quickly become trillionaires.

Where are all the trillionaires?

How should we then live?

If this is an accurate understanding of the world we live in — and I believe it is — how should we then live?

We inhabit a world in which reason is needed more than ever before, yet in which reason is so narrowly conceived that it drives out true understanding. For that we would have had to learn respect for the power of intuition, not as opposed to reason, but as both grounding it, and the means for it to fulfil its potential in making judgments in life.

Iain McGilchrist

We have three basic options:

Do not play the game. Ignore it.

Try to understand all of the complexity.

Wisely choose where to compress complexity.

Our partnership chooses option three, which is why we spend so much time seeking to be well-calibrated on the world we are in, questioning how we know what we know, debating how certain we can be of any of it, and selectively investing in assets that compress an enormous amount of complexity within themselves.

Compressing complexity into assets

In practical terms, this means investing in assets that are likely to do well regardless of the specifics.

We can try to predict winners in e-commerce, or we can invest in a scarce asset with a large lead in a niche with little competition and high barriers to entry.

We can try to predict the next thing that will grab consumers' attention, or we can observe that the price of attention is going up and invest in the few places that already have most of it.

We can try to predict winners in AI, or we can observe AI being most useful when it has the best context and own the very few places that already have most of that context.

We can try to fully understand the crucible of energy, compute, and crypto, or we can invest in a scarce asset that is at the nexus of all three.

And of course, when we can’t find great options (assets or prices), we can choose not to invest. The old rules still apply.

Compressing complexity into people

This all holds true for people, too. It is possible to observe people being well-calibrated on reality and adept at steering their business accordingly. Investing with these people is essentially compressing complexity into them.

This holds true for friends, as well. Too much time spent with those poorly calibrated on reality or those overly certain of their understanding of reality (we are all wrong often...the antidote is humility) both have unique risks and raise the odds of one being dissatisfied with the eventual outcomes.

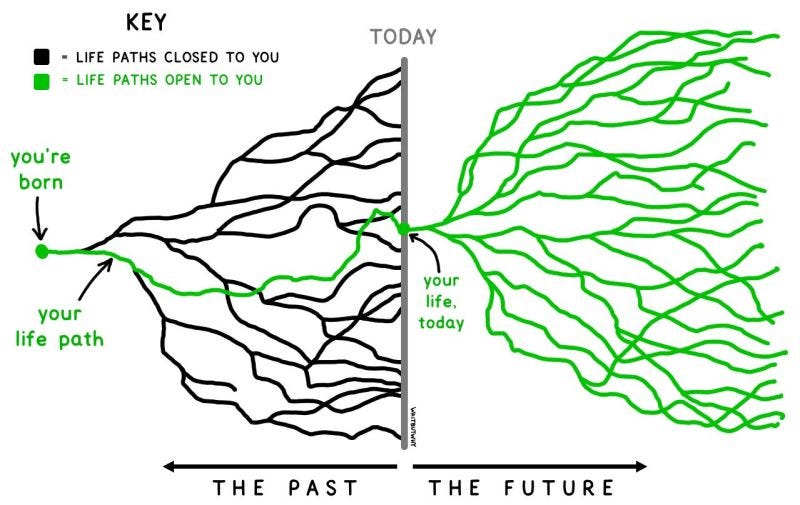

This all comes down to who one trusts to navigate the future. There are some assets so well positioned that they are likely to be successful in many future paths. Some people, too.1

Here’s another thought experiment I frequently consider: if Jeff Bezos lived his life 1,000 different times, in how many of them is he as successful as he is today? What about Warren Buffett? Elon Musk? Abraham Lincoln? Fred Rogers?

We want to be in the company of assets and people who would likely be successful should they get to live their lives a thousand time over.

Time is on my side. Yes it is?

Wise compression of complexity is how we minimize path-dependency in our investments. And when we do this, time becomes the scarcest asset in the world.

Mathematically, our partnership’s returns will be a function of the rate at which we can compound our capital raised to the power of the number of years we do so.

Return = (1 + Rate of Return) ^ Years of CompoundingA low rate of return will be disappointing, hence our focus on surviving (a 0% return never compounds) and pursuing power law potential (a very low rate of return doesn't compound into much, especially when it must beat inflation). But a low amount of time for compounding will also be disappointing.

The greatest public market returns over the past 100 years were from firms who sold tobacco, rocks, and railroads. They survived, had a decent rate of return, and an enormously long time to compound. The greatest public market returns over the past 30 years were from firms who digitized the world. They had a much higher rate of return vs. tobacco, rocks and railroads, but still required three decades of compounding to top the league tables.

This is why we say time is the scarcest asset in the world. It is the variable that dominates all others. It is the best filter for Quality with a capital-Q. It is the only thing we cannot get more of. And we don't even know how much of it we have.

In closing

Economy of time is surviving, evolving, and minimizing the odds that either of these get disrupted, thereby maximizing the time over which one can keep compounding.

Much of this resolves in wisely selecting where we compress complexity, and being well-suited for and well-structured to manage through the inevitable volatility that is a natural feature of a broken world, full of people oscillating between being humbled and being our own gods.

Thank you as always for the opportunity to compound trust with you. It is an honor to serve you.

Thank you to Steve, JD, Trevor, and Drex for feedback on early drafts!

All the best,

John

Founder and Managing Partner

In some ways, compression of complexity explains West Coast VC-style investing that tends to compress complexity into people vs. East Coast capital markets investing that tends to compress complexity into assets. As usual, our partnership seeks to occupy Maxwell, Nebraska — the location halfway between San Francisco and New York and conveniently close to Omaha.