This is the first entry in our Power Laws in Public Markets series.

This essay argues that the world is ruled by power laws, not averages.

Part 2 argues that economy of time is the primary force behind power laws.

Part 3 (forthcoming) defines cognitive leverage and how to spot power law potential.

Part 4 (forthcoming) offers a set of principles for operating in a world ruled by power laws.

Fellow Partners,

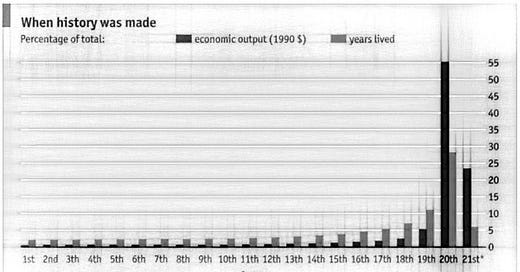

The 19th century saw the creation of twice as much value as the 18th century.

The 20th century saw the creation of more value than all of human history.

The 21st century is already nearing the total value creation of the 20th century and we’re less than a quarter of the way through it.

It’s a safe bet that more value will be created in the next decade than was created in the last decade.

Value creation is compressing.

Power laws rule the world

The above is a prime example of a power law outcome at work, and a great illustration of the fact that the world is ruled by power laws — not averages.

This has always been true. It is always under-appreciated.

Many — especially in venture capital — have rightly concluded that power law outcomes are what really move the needle. Ben Horowitz famously remarked that 97% of venture capital returns in any given year come from 15 investments. Having one of those positions in a portfolio is all that matters for the outcome of those funds.

This is also true far beyond venture capital.

Ben Graham spent his career inventing and practicing value investing and codified it in The Intelligent Investor. Late in life he admitted he made far more from one investment in a growth stock (GEICO) that broke all his value investing rules than all his other investments combined. Read that again.

This is true of Graham’s disciples, including Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger who have both commented that excluding their top 15 or so investments across their 70+ years of investing would give them unremarkable track records. By one estimate Buffett has owned about 400 stocks in his career. 15 of those are a mere 4%. Munger insists one is lucky to find just four good investment opportunities at any given time.

This is also true of Buffett disciples, including billionaire Bill Miller who — despite incredible performance as a value investor with many portfolios — has attributed most of his wealth to finding two investments early — Amazon and Bitcoin — and hanging on for the (very volatile) rides.

Zooming out, this is true within indexes as well. The top 5% of S&P 500 index firms have contributed 50% of the index gains in the past year. The bottom 2% have contributed 50% of the losses.

Sub-divide any portfolio (including our partnership) and one will find a similar pattern.

This implies an essential rule: only make investments that have the potential for power law outcomes. The magnitude of power law outcomes (10x, 100x, 1000x returns or more) is such that catching them, and hanging on when you do, is nearly all that matters.

Power laws rule the world.

Power law outcomes are playing out faster

We live in a world of complex non-linear change. Enormous improvements interact with each other to create ever-more enormous outcomes on ever-shorter timeframes.

Computers empowered us to digitize the sum of human knowledge. The internet empowered us to globally distribute it, and quickly and cheaply connect with each other. Smartphones put those capabilities in our pockets — all knowledge and many people, on-demand. Software, search and now artificial intelligence help us organize, access and distill this wealth of knowledge and connections into useful information.

For any innovator, business, or problem solver, the sum of all human knowledge is only a smartphone away. The implication of this level of connectivity to this depth of knowledge is only just beginning to be realized.

Thatcher Martin

The addition of on-demand, scalable infrastructure and growth in global population and wealth mean that there are far more people with outstanding value-creation ideas, the ability to tinker and experiment, and connect with people and resources to do so than at any other point in human history.

Cloud computing infrastructure is akin to giving every tinkerer in past technological revolutions access to immediately scalable and inexpensive textile mills, steam engines, steel furnaces, moving assembly lines, and microprocessors. Providing the masses the freedom to experiment unlocks the potential of technological breakthroughs in ways that were simply not possible in past technological revolutions.

Thatcher Martin

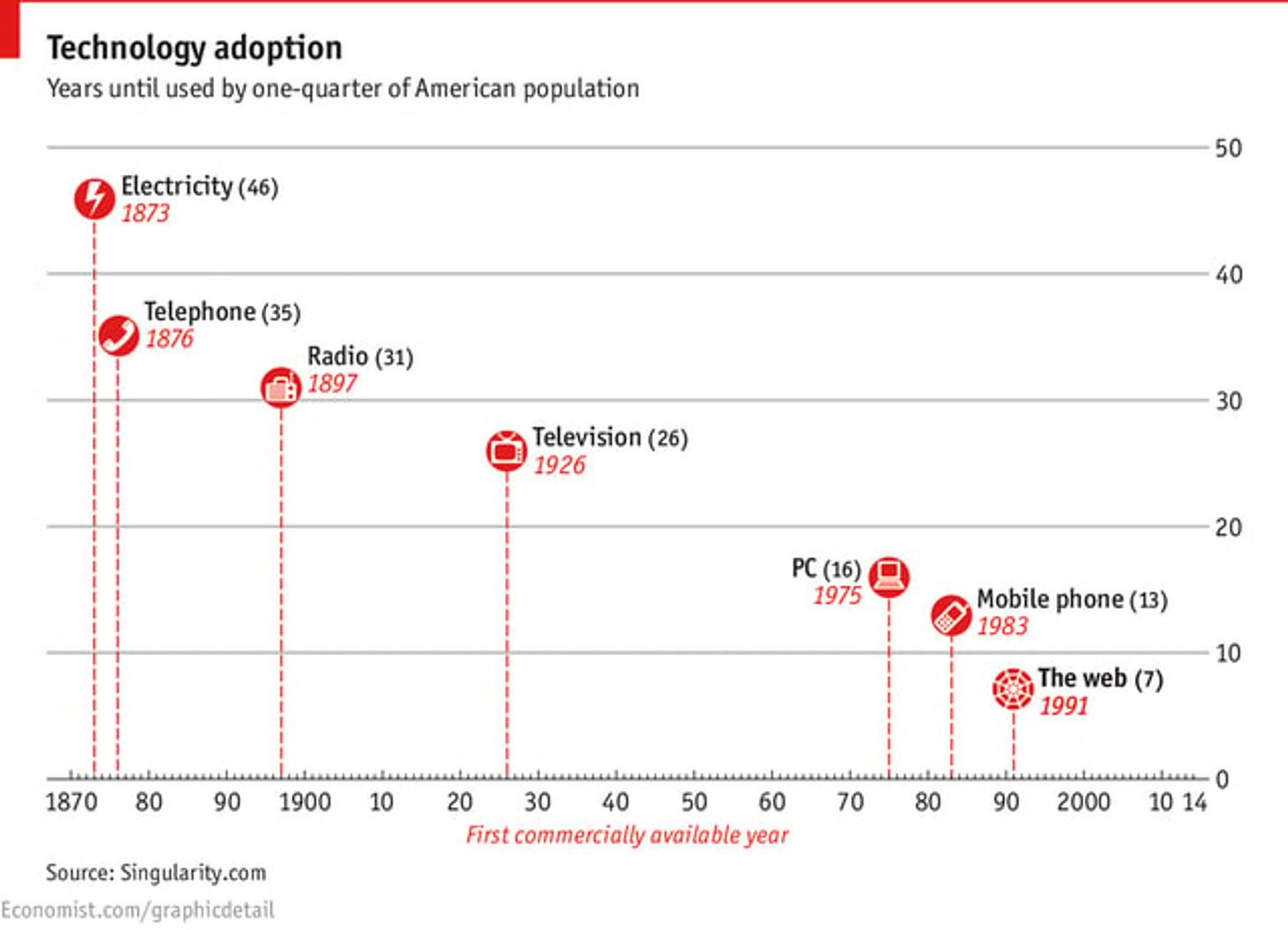

The addition of fast, inexpensive, and often free distribution enables adoption of the best value-creating ideas faster than ever.

Vaccines used to take decades to develop. Covid-19 vaccines took less than a year. Netflix took two years to get one million users; Facebook took 10 months; ChatGPT took 5 days.

Power laws outcomes are playing out faster.

Power laws outcomes are getting bigger

The magnitude of this reality is hard to see. It is even harder to intuit.

The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function.

Albert Allen Bartlett

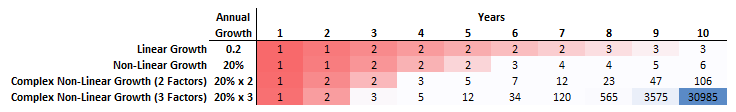

We are comfortable with linear change: A business able to create $100 of value and grow this by $20 each year will grow their value-creation capability to $300 in 10 years — a 3x increase.

Non-linear change is non-intuitive: A business able to create $100 of value and grow this by 20% each year will grow their value-creation capability to $600 in 10 years — a 6x increase.

Complex non-linear change fools just about everyone: A business able to create $100 of value and grow this by 20% each year, while also growing that growth capability by 20% each year, will grow their value-creation capability to $10,000 in 10 years — a 100x increase.

Adding a third 20% growth factor raises value-creation capability to $3,000,000 in 10 years — a 30,000x increase.

Only complex non-linear change — an increase in the rate-of-change of the rate-of-change — can explain the extreme value creation on the timescales that enables power law outcomes to be the dominant factor in investment success or failure. GEICO, Coca-Cola, Apple, Moody’s, Amazon, and Booking Holdings are all great examples of where this has occurred in public capital markets.

An outstanding product or service is essential. But beyond that, complex non-linear change must be at play.

GEICO benefitted from a 3x increase in households with two or more vehicles alongside a 3x reduction in households without cars.1 Coca-Cola benefitted from enormous growth in sugar addiction and enormous growth in international markets (an ever-expanding consumer base). Apple benefitted from most of the major technology trends of the past four decades, and supercharged returns with aggressive share buybacks. Moody’s benefitted from a massive increase in corporate debt issuance and the concurrent desire for businesses to assess economic, credit, and compliance risks. Amazon and Booking Holdings became stars of complex forces far stronger than themselves: consumer empowerment and choice.

All of these firms also benefitted from population and wealth growth.

These superb investment outcomes were the result of complex non-linear changes that in aggregate explains how the human species will create far more value in the next few decades than in the sum of human history to date.

If progress is real despite our whining, it is…because we are born to a richer heritage, born on a higher level of that pedestal which the accumulation of knowledge and art raises as the ground and support of our being.

Will and Ariel Durant

Notice, too, that scale has generally increased with each decade. Non-linear change can produce immense outcomes. Complex non-linear change means power laws are not only playing out faster, but are also getting bigger. It is unsurprising that businesses are bigger today than at any other point in our species.

Power laws outcomes are getting bigger.

Power laws outcomes are becoming more accessible to innovators

The conditions that allow power law outcomes to play out faster and get bigger also make power law outcomes more accessible to innovators.

Historically to innovate most had to take enormous personal risk — for example, mortgaging their house to get startup capital, and losing that house to the bank if their endeavor failed.

Beginning with the creation of the joint stock company and business insurance in the early 17th century, liability limitations have increasingly separated personal risk from enterprise risk. (The latest popular form in America, the Limited Liability Company, only came about in 1977 and gained popularity in the 1990s.) The result is an enormous incentive for millions more to innovate.

The amplitude of innovations is also accelerating. In 1900 a property survey team could measure 200 points per day to plan land use and construction. By 2020 this number had risen to a paltry 500 points. The combination of drone aircraft, aerial imaging, and software has recently brought this up to 20 million points per hour.

Such virtualization of atoms into bits means innovators can test and refine far more permutations of innovations, as well as permutations of innovations combined into different architectures (e.g., various semiconductors combined to create computers), which are what tend to have the big catalyzing rippling effects.

These realities substantially amplify the value creation potential of each innovator.

What the most ambitious people choose to do with their lives has a profound impact on society, the economy and culture.

Matt Clifford

Because of these amplifying effects, technology entrepreneurship is becoming the dominant “technology of ambition”. (Prior technologies of ambition included literacy in the pre-modern world, military command in the 18th and 19th centuries, and finance, law and politics in the 20th century.) Many of the most capable humans are likely to follow this path because it maximizes their ability to have impact.

Power laws outcomes are becoming more accessible to innovators.

Power laws outcomes are becoming more accessible to public market investors

The conditions that allow power laws to play out faster, get bigger, and become more accessible to innovators also make power law outcomes more accessible to public market investors.

First, the ability to self-organize and raise capital is higher than ever. This broadens the investment landscape.

Second, assets and asset classes historically restricted to the well-connected and well-funded have become publicly accessible. There’s even a new asset class that is default-public (a first in history) and substantial formalization of others. This broadens the accessible investment landscape.

Third, we are coming out of a cycle in which private market investors were able to use abundant capital to keep power law outcome investments out of public markets for longer, resulting in much higher valuations at IPO and much less value created after those firms went public. For example, FAANG+ stocks with IPO valuations above $1 billion have had only half of the annualized return after going public vs. FAANG+ stocks with IPO valuations below $1 billion2. The latter group created far more of their value in public markets.

Another perspective: FAANG+ stocks have created about $30 billion of value per year since going public.

Those with IPO valuations below $1 billion created about $100 million of value per year before becoming publicly accessible to investors, and the rest in public markets, resulting in much higher public market returns.

By contrast, those with IPO valuations above $1 billion created about $5 billion of value per year before becoming publicly accessible to investors. Much more of their value creation took place in private markets, which subsequently reduced their public market returns.This argument has its flaws but the broad point stands: well funded private capital markets can suppress value creation in public markets.

Higher interest rates and economic uncertainty are likely to result in greater use of public capital markets since public markets are deeper and spread risk more broadly, and in this environment, innovative firms and their private backers are likely to prefer earlier IPOs to larger later-stage funding rounds.

The result will be the ability to access formerly private opportunities in public markets, and a likelihood that much more value will be created in public markets.

Power law outcomes are becoming more accessible to public market investors.

Part 2

The magnitude of power law outcomes has always been such that catching them, and hanging on when you do, is nearly all that matters. That they are playing out faster, getting bigger, and becoming more accessible is an added benefit of our time.

So how do we catch them, and manage risk as we pursue them?

Those are the subjects of the following entries in this series.

All the best,

John

Founder and Managing Partner

https://transportgeography.org/contents/chapter8/urban-transport-challenges/household-vehicles-united-states/

FAANG+ firms that listed with valuations below $1 billion: Microsoft, Amazon, Nvidia, and Netflix. Their average annualized return since IPO has been 31%.

FAANG+ firms that listed with valuations above $1 billion: Apple, Google, Facebook (Meta), and Snowflake. Their average annualized return since IPO has been 17%.

How is power law different than compounding or leverage? For example, companies like Amazon used leverage of code and internet to grow as compared.

I am trying to store "power law" alongside my other mental concepts of compounding or leverage. Thus, I would like your clarification and additional notes with a real example.

Thank you for sharing this with the world!